History of photography

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The metal-based daguerreotype process soon had some competition from the paper-based calotype negative and salt print processes invented by Henry Fox Talbot. Subsequent innovations reduced the required camera exposure time from minutes to seconds and eventually to a small fraction of a second; introduced new photographic media which were more economical, sensitive or convenient, including roll films for casual use by amateurs; and made it possible to take pictures in natural color as well as in black-and-white.

The commercial introduction of computer-based electronic digital cameras in the 1990s soon revolutionized photography. During the first decade of the 21st century, traditional film-based photochemical methods were increasingly marginalized as the practical advantages of the new technology became widely appreciated and the image quality of moderately priced digital cameras was continually improved.

Contents

Etymology

The coining of the word "photography" is usually attributed to Sir John Herschel in 1839. It is based on the Greek φῶς (phos), (genitive: phōtós) meaning "light", and γραφή (graphê), meaning "drawing, writing", together meaning "drawing with light".[2]Technological background

Photography is the result of combining several different technical discoveries. Long before the first photographs were made, Chinese philosopher Mo Ti and Greek mathematicians Aristotle and Euclid described a pinhole camera in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[3][4] In the 6th century CE, Byzantine mathematician Anthemius of Tralles used a type of camera obscura in his experiments[5]Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965 in Basra – c. 1040 in Cairo) studied the camera obscura and pinhole camera,[4][6] Albertus Magnus (1193/1206–80) discovered silver nitrate, and Georges Fabricius (1516–71) discovered silver chloride. Daniel Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1568. Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694. The novel Giphantie (by the French Tiphaigne de la Roche, 1729–74) described what could be interpreted as photography.

Development of chemical photography

Monochrome process

Earliest known surviving heliographic engraving, 1825, printed from a metal plate made by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce with his "heliographic process".[7] The plate was exposed under an ordinary engraving and copied it by photographic means. This was a step towards the first permanent photograph from nature taken with a camera obscura.

"Boulevard du Temple", a daguerreotype made by Louis Daguerre in 1838, is generally accepted as the earliest photograph to include people. It is a view of a busy street, but because the exposure time was at least ten minutes the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men near the bottom left corner, one apparently having his boots polished by the other, stayed in one place long enough to be visible.

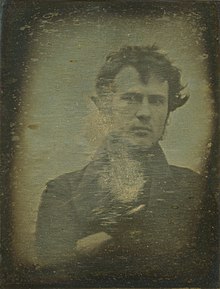

Robert Cornelius, self-portrait, Oct. or Nov. 1839, approximate quarter plate daguerreotype. The back reads, "The first light picture ever taken."

One of the oldest photographic portraits known, made by Joseph Draper of New York, in 1839[10] or 1840, of his sister, Dorothy Catherine Draper.

A photograph of William Mansel (1838-1866) thought to be the first smile ever captured on Camera. Taken in Wales by Mary Dillwyn, 1853

In partnership, Niépce (in Chalon-sur-Saône) and Louis Daguerre (in Paris) refined the bitumen process,[13] substituting a more sensitive resin and a very different post-exposure treatment that yielded higher-quality and more easily viewed images. Exposure times in the camera, although somewhat reduced, were still measured in hours.[9]

In 1833 Niépce died suddenly, leaving his notes to Daguerre. More interested in silver-based processes than Niépce had been, Daguerre experimented with photographing camera images directly onto a mirror-like silver-surfaced plate that had been fumed with iodine vapor, which reacted with the silver to form a coating of silver iodide. As with the bitumen process, the result appeared as a positive when it was suitably lit and viewed. Exposure times were still impractically long until Daguerre made the pivotal discovery that an invisibly slight or "latent" image produced on such a plate by a much shorter exposure could be "developed" to full visibility by mercury fumes. This brought the required exposure time down to a few minutes under optimum conditions. A strong hot solution of common salt served to stabilize or fix the image by removing the remaining silver iodide. On 7 January 1839, this first complete practical photographic process was announced at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences,[14] and the news quickly spread. At first, all details of the process were withheld and specimens were shown only at Daguerre's studio, under his close supervision, to Academy members and other distinguished guests.[15] Arrangements were made for the French government to buy the rights in exchange for pensions for Niépce's son and Daguerre and present the invention to the world (with the de facto exception of Great Britain) as a free gift.[16] Complete instructions were published on 19 August 1839.[17]

After reading early reports of Daguerre's invention, William Henry Fox Talbot, who had succeeded in creating stabilized photographic negatives on paper in 1835, worked on perfecting his own process. In early 1839 he acquired a key improvement, an effective fixer, from John Herschel, the astronomer, who had previously shown that hyposulfite of soda (commonly called "hypo" and now known formally as sodium thiosulfate) would dissolve silver salts.[18] News of this solvent also reached Daguerre, who quietly substituted it for his less effective hot salt water treatment.[19]

In 1839, John Herschel made the first glass negative, but his process was difficult to reproduce. Slovene Janez Puhar invented a process for making photographs on glass in 1841; it was recognized on June 17, 1852 in Paris by the Académie Nationale Agricole, Manufacturière et Commerciale.[21] In 1847, Nicephore Niépce's cousin, the chemist Niépce St. Victor, published his invention of a process for making glass plates with an albumen emulsion; the Langenheim brothers of Philadelphia and John Whipple and William Breed Jones of Boston also invented workable negative-on-glass processes in the mid-1840s.[22]

In 1851 Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process.[citation needed] Photographer and children's author Lewis Carroll used this process. (Carroll refers to the process as "Tablotype" [sic] in the story "A Photographer's Day Out")[23]

Nineteenth-century experimentation with photographic processes frequently became proprietary. The German-born, New Orleans photographer Theodore Lilienthal successfully sought legal redress in an 1881 infringement case involving his "Lambert Process" in the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Popularization

Mid 19th century "Brady stand" photo model's armrest table, meant to keep portrait models more still during long exposure times (studio equipment nicknamed after the famed US photographer, Mathew Brady)

In 1847, Count Sergei Lvovich Levitsky designed a bellows camera that significantly improved the process of focusing. This adaptation influenced the design of cameras for decades and is still found in use today in some professional cameras. While in Paris, Levitsky would become the first to introduce interchangeable decorative backgrounds in his photos, as well as the retouching of negatives to reduce or eliminate technical deficiencies.[citation needed] Levitsky was also the first photographer to portray a photo of a person in different poses and even in different clothes (for example, the subject plays the piano and listens to himself).[citation needed]

Roger Fenton and Philip Henry Delamotte helped popularize the new way of recording events, the first by his Crimean war pictures, the second by his record of the disassembly and reconstruction of The Crystal Palace in London. Other mid-nineteenth-century photographers established the medium as a more precise means than engraving or lithography of making a record of landscapes and architecture: for example, Robert Macpherson's broad range of photographs of Rome, the interior of the Vatican, and the surrounding countryside became a sophisticated tourist's visual record of his own travels.

By 1849, images captured by Levitsky on a mission to the Caucasus were exhibited by the famous Parisian optician Chevalier at the Paris Exposition of the Second Republic as an advertisement of their lenses. These photos would receive the Exposition's gold medal; the first time a prize of its kind had ever been awarded to a photograph.[citation needed]

That same year in 1849 in his St. Petersburg, Russia studio Levitsky would first propose the idea to artificially light subjects in a studio setting using electric lighting along with daylight. He would say of its use, "as far as I know this application of electric light has never been tried; it is something new, which will be accepted by photographers because of its simplicity and practicality".[citation needed]

In 1851, at an exhibition in Paris, Levitsky would win the first ever gold medal awarded for a portrait photograph.[citation needed]

In America, by 1851 a broadside by daguerreotypist Augustus Washington was advertising prices ranging from 50 cents to $10.[25] However, daguerreotypes were fragile and difficult to copy. Photographers encouraged chemists to refine the process of making many copies cheaply, which eventually led them back to Talbot's process.

Ultimately, the photographic process came about from a series of refinements and improvements in the first 20 years. In 1884 George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, developed dry gel on paper, or film, to replace the photographic plate so that a photographer no longer needed to carry boxes of plates and toxic chemicals around. In July 1888 Eastman's Kodak camera went on the market with the slogan "You press the button, we do the rest". Now anyone could take a photograph and leave the complex parts of the process to others, and photography became available for the mass-market in 1901 with the introduction of the Kodak Brownie.

Color process

Main article: Color photography

The first durable color photograph was a set of three black-and-white photographs taken through red, green and blue color filters and shown superimposed by using three projectors with similar filters. It was taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861 for use in a lecture by the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who had proposed the method in 1855.[26] The photographic emulsions then in use were insensitive to most of the spectrum, so the result was very imperfect and the demonstration was soon forgotten. Maxwell's method is now most widely known through the early 20th century work of Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. It was made practical by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel's 1873 discovery of a way to make emulsions sensitive to the rest of the spectrum, gradually introduced into commercial use beginning in the mid-1880s.

Two French inventors, Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charles Cros, working unknown to each other during the 1860s, famously unveiled their nearly identical ideas on the same day in 1869. Included were methods for viewing a set of three color-filtered black-and-white photographs in color without having to project them, and for using them to make full-color prints on paper.[27]

The first widely used method of color photography was the Autochrome plate, commercially introduced in 1907. It was based on one of Louis Ducos du Hauron's ideas: instead of taking three separate photographs through color filters, take one through a mosaic of tiny color filters overlaid on the emulsion and view the results through an identical mosaic. If the individual filter elements were small enough, the three primary colors would blend together in the eye and produce the same additive color synthesis as the filtered projection of three separate photographs. Autochrome plates had an integral mosaic filter layer composed of millions of dyed potato starch grains. Reversal processing was used to develop each plate into a transparent positive that could be viewed directly or projected with an ordinary projector. The mosaic filter layer absorbed about 90 percent of the light passing through, so a long exposure was required and a bright projection or viewing light was desirable. Competing screen plate products soon appeared and film-based versions were eventually made. All were expensive and until the 1930s none was "fast" enough for hand-held snapshot-taking, so they mostly served a niche market of affluent advanced amateurs.

A new era in color photography began with the introduction of Kodachrome film, available for 16 mm home movies in 1935 and 35 mm slides in 1936. It captured the red, green and blue color components in three layers of emulsion. A complex processing operation produced complementary cyan, magenta and yellow dye images in those layers, resulting in a subtractive color image. Maxwell's method of taking three separate filtered black-and-white photographs continued to serve special purposes into the 1950s and beyond, and Polachrome, an "instant" slide film that used the Autochrome's additive principle, was available until 2003, but the few color print and slide films still being made in 2015 all use the multilayer emulsion approach pioneered by Kodachrome.

Development of digital photography

Main article: Digital photography

In 1957, a team led by Russell A. Kirsch at the National Institute of Standards and Technology developed a binary digital version of an existing technology, the wirephoto drum scanner, so that alphanumeric characters, diagrams, photographs and other graphics could be transferred into digital computer memory. One of the first photographs scanned was a picture of Kirsch's infant son Walden. The resolution was 176x176 pixels with only one bit per pixel, i.e., stark black and white with no intermediate gray tones, but by combining multiple scans of the photograph done with different black-white threshold settings, grayscale information could also be acquired.[28]The charge-coupled device (CCD) is the image-capturing optoelectronic component in first-generation digital cameras. It was invented in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at AT&T Bell Labs as a memory device. The lab was working on the Picturephone and on the development of semiconductor bubble memory. Merging these two initiatives, Boyle and Smith conceived of the design of what they termed "Charge 'Bubble' Devices". The essence of the design was the ability to transfer charge along the surface of a semiconductor. It was Dr. Michael Tompsett from Bell Labs however, who discovered that the CCD could be used as an imaging sensor. The CCD has increasingly been replaced by the active pixel sensor (APS), commonly used in cell phone cameras.

- 1973 - Fairchild Semiconductor releases the first large image-capturing CCD chip: 100 rows and 100 columns.[29]

- 1975 - Bryce Bayer of Kodak develops the Bayer filter mosaic pattern for CCD color image sensors

- 1986 - Kodak scientists develop the world's first megapixel sensor.

See also

- History of the camera

- History of Photography (academic journal)

- History of photographic lens design

- Timeline of photography technology

- List of basic photography topics

- Photography by indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Women in photography

References

- Seizing the Light: A History of Photography By Robert Hirsch

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- "Light Through the Ages".

- Robert E. Krebs (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32433-6.

- Alistair Cameron Crombie, Science, optics, and music in medieval and early modern thought, p. 205

- Wade, Kaitlyjj; Finger, Stanley (2001). "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective". Perception 30 (10): 1157–77. doi:10.1068/p3210. PMID 11721819.

- "The First Photograph — Heliography". Retrieved 29 September 2009.

from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ...In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate... The sunlight passing through... This first permanent example... was destroyed... some years later.

- Litchfield, R. 1903. "Tom Wedgwood, the First Photographer: An Account of His Life." London, Duckworth and Co. See Chapter XIII. Includes the complete text of Humphry Davy's 1802 paper, which is the only known contemporary record of Wedgwood's experiments. (Retrieved 7 May 2013 via archive.org).

- Niépce Museum history pages

- Folpe, Emily Kies (2002). It Happened on Washington Square. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-8018-7088-7.

- [1] By Christine Sutton

- Niépce House Museum: Invention of Photography, Part 3. Retrieved 25 May 2013. The traditional estimate of eight or nine hours originated in the 1950s and is based mainly on the fact that sunlight strikes the buildings as if from an arc across the sky, an effect which several days of continuous exposure would also produce.

- "Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography". Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- (Arago, François) (1839) "Fixation des images qui se forment au foyer d'une chambre obscure" (Fixing of images formed at the focus of a camera obscura), Comptes rendus, 8 : 4-7.

- e.g., a 9 May 1839 showing to John Herschel, documented by Herschel's letter to WHF Talbot. See the included footnote #1 (by Larry Schaaf?) for context. Accessed 11 September 2014.

- Daguerre (1839), pages 1-4.

- See:

- (Arago, François) (1839) "Le Daguerreotype", Comptes rendus, 9 : 250-267.

- Daguerre, Historique et description des procédés du Daguerréotype et du diorama [History and description of the processes of the daguerreotype and diorama] (Paris, France: Alphonse Giroux et Cie., 1839).

- John F. W. Herschel (1839) "Note on the art of photography, or the application of the chemical rays of light to the purposes of pictorial representation," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 4 : 131-133. On page 132 Herschel mentions the use of hyposulfites.

- Daguerre, Historique et description des procédés du Daguerréotype et du diorama [History and description of the processes of the daguerreotype and diorama] (Paris, France: Alphonse Giroux et Cie., 1839). On page 11, for example, Daguerre states: "Cette surabondance contribue à donner des tons roux, même en enlevant entièrement l'iode au moyen d'un lavage à l'hyposulfite de soude ou au sel marin." (This overabundance contributes towards giving red tones, even while completely removing the iodine by means of a rinse in sodium hyposulfite or in sea salt.)

- Improvement in photographic pictures, Henry Fox Talbot, United States Patent Office, patent no. 5171, June 26, 1847.

- "Life and work of Janez Puhar | (accessed December 13, 2009)".

- Michael R. Peres (2007). The Focal encyclopedia of photography: digital imaging, theory and applications, history, and science. Focal Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-240-80740-9.

- The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll, from the Random House Modern Library

- Levenson, G. I. P (May 1993). "Berkeley, overlooked man of photo science". Photographic Journal 133 (4): 169–71.

- Loke, Margarett (July 7, 2000). "Photography review; In a John Brown Portrait, The Essence of a Militant". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- James Clerk Maxwell (2003). The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell. Courier Dover Publications. p. 449. ISBN 0-486-49560-4.

- Brian, Coe (1976). The Birth of Photography. Ash & Grant. ISBN 0-904069-07-9.

- SEAC and the Start of Image Processing at the National Bureau of Standards - Earliest Image Processing

- Janesick, James R (2001). Scientific Charge Coupled Devices. SPIE Press. ISBN 0-8194-3698-4.

0 comments:

Post a Comment